While there is a section on applicable taxes in the Buyer’s Guide: How to Buy Land in Nova Scotia, the topic is worth a deeper dive. That is particularly true due to the recent increase in capital gains inclusion rates that became effective across Canada in 2024.

Deed Transfer Taxes

The most common tax to be aware of is the Municipal Deed Transfer Tax (MDTT). Municipal Deed Transfer Tax rates are set by each municipality, and generally range from 1.0% to 1.5% of the sale price of the property. At the bottom of the post, you’ll find the applicable MDTT rate for each municipality in Nova Scotia. Municipal Deed Transfer Taxes are collected on behalf of the municipality through Land Registration Offices when the deed is registered/recorded.

Provincial Non-Resident Deed Transfer Taxes (PDTT)

Here’s the fun part for out-of-province buyers. As of April, 2022, property buyers who are not residents of Nova Scotia must pay an additional 5% in deed transfer tax. This is in addition to the municipal deed transfer tax. The PDTT applies to all residential properties with 3 dwelling units or less, including vacant land considered to be residential property.

NOTE: the PDTT will be 5% in most cases, but it is actually the greater of the assessed value of the property, or 5% tax on the sale price of the property.

Capital Gains Tax

When selling vacant land, capital gains tax may apply. The difference between the sale price and the original purchase price, minus any eligible expenses, is considered a capital gain. This tax is not part of the purchase and sale process; instead, it’s a requirement as part of the tax return filing of the seller. Capital gains are reported at tax time using Schedule 3, Capital Gains (or Losses).

There are some exemptions. If you’re selling your principal residence – the home you live in – you are exempt from capital gains. But if it’s a second home, a cottage, or just a big ol’ parcel of land you own, you’re on the hook for capital gains.

When you complete the Schedule 3, you’ll enter your original purchase price, sale price, and any eligible expenses including selling and closing costs. The resulting gain after those deductions is what you’ll pay tax on. The tax rate on your first $250,000 of capital gains in a calendar year is taxed at 50%. Any amounts above that are taxed at 67%. For a quick calculation of how much tax you may owe, try the Capital Gains Tax Calculator from Lari.ca.

Taxes Due to an Estate on Death

I’m going to touch on some possible tax events to your estate in the event of your death. Sorry to get morbid, but I do think there’s a real awareness gap here. Land is a funny type of asset. In many cases, it’s passed on to family through the generations. Meanwhile, the value of that land is increasing and, in the event of death it can trigger … you guessed it… capital gains tax.

Upon the death of the owner, the property is deemed to be disposed of at its fair market value. Any resulting capital gain must be reported on the final tax return of the deceased, potentially leading to a significant tax bill. The land can be transferred to a surviving spouse if one exists – this basically defers the tax until a future date when the surviving spouse passes away.

To give a quick example, in 1990, Paul inherits a 250-acre woodlot from his parents. Taxes are all paid up by the time the deed transfer is completed, so Paul was not impacted by that and didn’t need to get involved. He spends decades enjoying the woodlot and trails with his family. Meantime, the market is driving real estate prices much higher in the area. Fast forward to today and Paul has passed away. Diving into his estate, his son is shocked at the extent of the capital gain on that land.

- Original market value (1990): $40,000

- Current market value (2024): $350,000

- Capital gain tax payable: $165,020

Effectively, the cost of keeping that land in the family is $165,020 which will be deducted from the assets of Paul’s estate and significantly reduce the funds that his son inherits. These are just pretend figures of course, but I feel this scenario is quite real for many people who may not be aware of the implications.

There are estate planning strategies that might help you reduce the ultimate tax bill if you have substantial land assets. Those are beyond my scope of advisement and I’d recommend talking to a good financial planner or accountant.

GST/HST on Sales of Vacant Land

I’ve written on this topic in the Buyer’s Guide: How to Buy Land in Nova Scotia, so I won’t duplicate that here. In a nutshell, if the land being sold is owned by an individual and was used solely for personal use, GST/HST does not need to be charged or collected from the seller. There are nuances to this including land that has been subdivided into multiple portions. For a good source straight from the Government, read the info here.

Property Taxes on Nova Scotia Land

Of course, for any owner of Nova Scotia land, there are property taxes to be paid each year. I’ve written a fair bit about how property is valued and the impact on your taxes in my post called Your Property Assessment and Nova Scotia Property Tax.

To wrap up this topic, you will find the list of Nova Scotia municipal deed transfer tax rates below. And here are links to other topics on buying land in Nova Scotia that might interest you:

- Buying Land in Nova Scotia: Tips for Foreign Investors

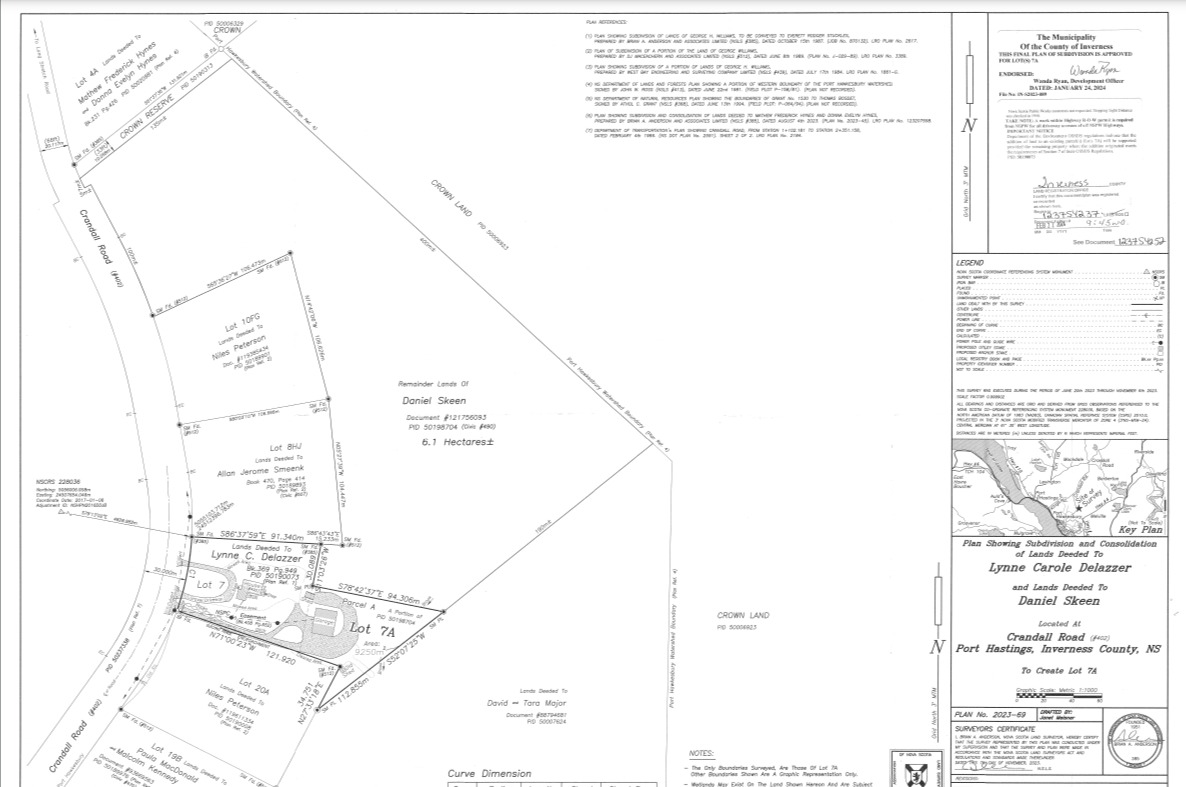

- The value of a land survey

- Nova Scotia zoning maps and land use bylaws

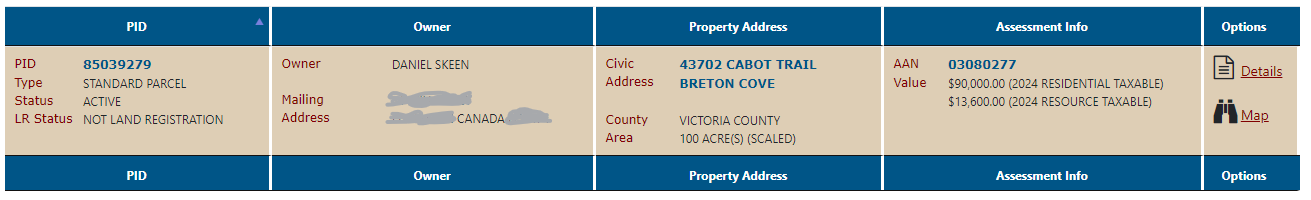

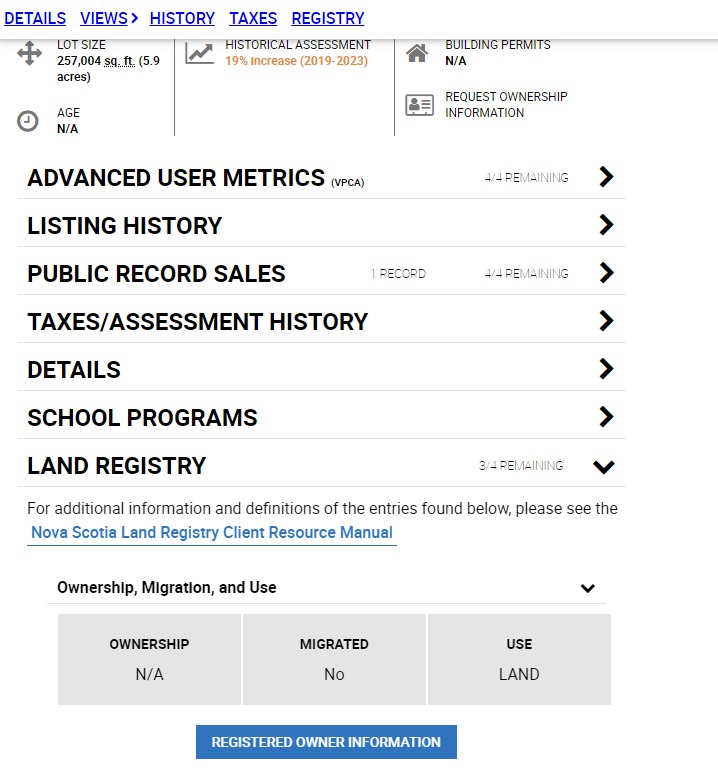

- Property Online and conducting Nova Scotia Title Searches

- Nova Scotia woodlot management

- Your property assessment and Nova Scotia property tax

- How to migrate property in Nova Scotia

- Nova Scotia land developer’s guide

- Sample purchase and sale agreement for private land sales

- Good (and bad!) Questions to ask when Buying Land

Municipal Deed Transfer Tax Rates

This data is current as of July, 2024. Municipal tax rates can change over time. For a current snapshot, visit the Provincial website.

| County | Municipality | Rate | Payable at LRO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annapolis | Municipality of the County of Annapolis | 1.5% | Kentville |

| Annapolis | Town of Annapolis Royal | 1.5% | Kentville |

| Annapolis | Town of Middleton | 1.5% | Kentville |

| Antigonish | Municipality of the County of Antigonish | 1.0% | Amherst |

| Antigonish | Town of Antigonish | 1.5% | Amherst |

| Cape Breton | Cape Breton Regional Municipality | 1.5% | Sydney |

| Colchester | Municipality of Colchester | 1.5% | Amherst |

| Colchester | Town of Stewiacke | 1.0% | Amherst |

| Colchester | Town of Truro | 1.0% | Amherst |

| Cumberland | Municipality of the County of Cumberland | 1.5% | Amherst |

| Cumberland | Town of Amherst | 1.25% | Amherst |

| Cumberland | Town of Oxford | 1.5% | Amherst |

| Digby | Municipality of the District of Clare | 1.0% | Kentville |

| Digby | Municipality of the District of Digby | 1.0% | Kentville |

| Digby | Town of Digby | 1.5% | Kentville |

| Guysborough | Municipality of the District of Guysborough | 1.0% | Sydney |

| Guysborough | Municipality of the District of St. Mary’s | 1.25% | Sydney |

| Guysborough | Town of Mulgrave | 0.5% | Sydney |

| Halifax | Halifax Regional Municipality | 1.5% | Halifax |

| Hants | Municipality of the District of Hants East | 1.5% | Kentville |

| Hants | West Hants Regional Municipality | 1.5% | Kentville |

| Inverness | Municipality of the County of Inverness | 1.5% | Sydney |

| Inverness | Town of Port Hawkesbury | 1.5% | Sydney |

| Kings | Municipality of the County of Kings | N/A | N/A |

| Kings | Town of Berwick | 1.0% | Kentville |

| Kings | Town of Kentville | 1.5% | Kentville |

| Kings | Town of Wolfville | 1.5% | Kentville |

| Lunenburg | Municipality of the District of Chester | 1.5% | Bridgewater |

| Lunenburg | Municipality of the District of Lunenburg | 1.25% | Bridgewater |

| Lunenburg | Town of Bridgewater | 1.5% | Bridgewater |

| Lunenburg | Town of Lunenburg | 1.5% | Bridgewater |

| Lunenburg | Town of Mahone Bay | 1.5% | Bridgewater |

| Pictou | Municipality of the County of Pictou | 1.0% | Amherst |

| Pictou | Town of New Glasgow | 1.0% | Amherst |

| Pictou | Town of Pictou | 1.0% | Amherst |

| Pictou | Town of Stellarton | 1.0% | Amherst |

| Pictou | Town of Trenton | 1.0% | Amherst |

| Pictou | Town of Westville | 1.0% | Amherst |

| Queens | Region of Queens Municipality | 1.5% | Bridgewater |

| Richmond | Municipality of the County of Richmond | 1.5% | Sydney |

| Shelburne | Municipality of the District of Barrington |

1.5% |